June 9, 2017

Day 26: Di Bray, Museums Victoria

Day 26: Di Bray, Museums Victoria

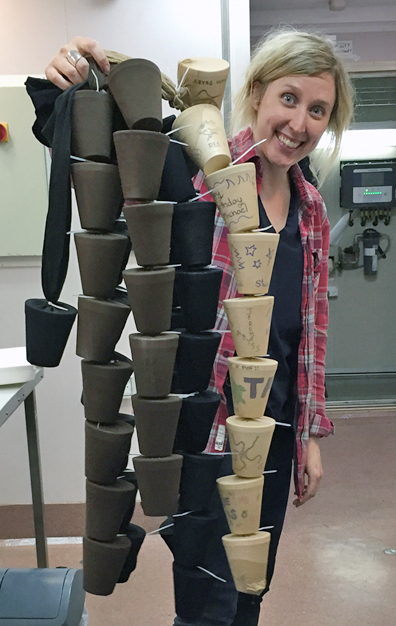

Lately we’ve been partaking in a long-standing tradition of oceanographic research voyages – sending Styrofoam cups to the depths of the ocean – this time to 4000 metres on the abyssal plain.

Before their journey to the abyss, the cups, complete with gorgeous drawings of deep-sea critters, ships, kids’ names, and even teddy bears, plus a bit of paper towel inside each to hold their shape, were pushed into long-discarded stockings. Usually, they’d hitch a ride on the CSIRO RV Investigator’s CTD probe: a high-tech instrument used to record conductivity, temperature and depth. But, we’re not using the CTD on this voyage, so it was the Brenke sled’s turn to carry them below.

Once safely secured to the Brenke’s frame with trusty cable ties – looking a bit like weird sausages strung together – the sled was gently deployed over the stern. Several hours later, as always, we excitedly awaited the Brenke’s return – imagining the amazing animals we’d see – and wondering how our cups had fared. There they were hanging off the Brenke: soggy limp stockings still protecting our tiny shrunken treasures.

Why do the cups shrink? Well, Styrofoam, or polystyrene foam, is mostly air – or plastic with air forced into it – which is why it weighs so little. As the cups descend, increasing pressures compress the polystyrene, forcing out the tiny air bubbles.

When people talk of pressure they often refer to atmospheric pressure. At sea level, the earth’s atmosphere presses on everything, including us, at a rate of just over one kilogram per square centimetre. This equals one 'atmosphere' of pressure. On the summit of Mt Everest, the atmospheric pressure is about one-third that found at sea level.

In the ocean, the deeper the water the greater the pressure. Water pressure increases by one atmosphere for every 10 m of depth, so at a depth of 10 m, the pressure is two atmospheres: twice that experienced at sea level. And, at a depth of 4000 m, our cups withstood (kind of) a bit more than 400 atmospheres of pressure – or more than 400 times the pressure at sea level. That’s a lot of pressure!

And it’s not just like the water pressure is squashing the cups from above. The pressure is everywhere, pushing from above, sideways and below, which is why the cups retain their shape, rather than looking like they’ve been run over by stampeding bunch of elephants.

It’s difficult to imagine how anything can survive down there without being crushed, especially for us humans who can only explore the deep sea inside a submersible (wouldn’t you love to do that?). So how is it possible for animals that either live in the deep sea, or dive down from the surface, to survive such intense pressure – especially those whales that dive to depths of about 3000 m?

When we dive below, we feel the water pressure compressing the air in our bodies, especially in our ears and sinuses. Most deep sea animals have no air spaces in their bodies; they’re mostly water which cannot be compressed. And the lungs of whales collapse when they dive deep, so, again there are no problematic airspaces.

Deep sea fishes have slow metabolisms and watery flesh which helps them cope with the pressure and the cold. Although some abyssal fishes have gas-filled swim bladders used for buoyancy, the gas inside is at the same pressure as the water outside, so the swim bladder doesn’t collapse. They have evolved to live in extreme environments, and they can’t live in ‘our world’. In fact, no-one has managed to keep deep sea fishes alive in aquaria for more than a few days, despite keeping them under pressure in really cold water.

It’s all much more complicated than this, but you get the idea . . .

Now, perhaps you’ll take a minute to think of all the amazing critters down there, including spiky crabs, sea anemones, corals, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, octopuses and weird fishes. The average depth of the ocean is about 3.6 kilometres, so there’s lots of abyssal plain down there, and lots of animals too. For them, near freezing temperatures and extreme pressures are just a normal part of life.

- Log in to post comments